August 4, 2013

Passion for Place reviewed by Jonah Raskin for the blog of BOOM: A Journal of California -- A University of California Press publication --

Like rivers, books can take time to reach their destinations. Published in 2012 after years in the making, Passion for Place—a compendium of art, essays, and interviews—is finding a niche close to the river that inspired it.

Paola Fiorelle Berthoin, the editor and driving force behind the book, is taking the book this August, September, and October, along with her own paintings and photographs, to events around Monterey County. The literary Carmelites Mary Austin and George Sterling, who lived in the watershed a hundred years ago, would likely join the festivities if they were around today. So would their summer guests, Jack and Charmian London, who often visited from Sonoma. Jack London raved about Carmel; he’d probably rave about Passion for Place. Like his best books, it takes readers on a journey, in this case inland, upstream, and into a watershed.

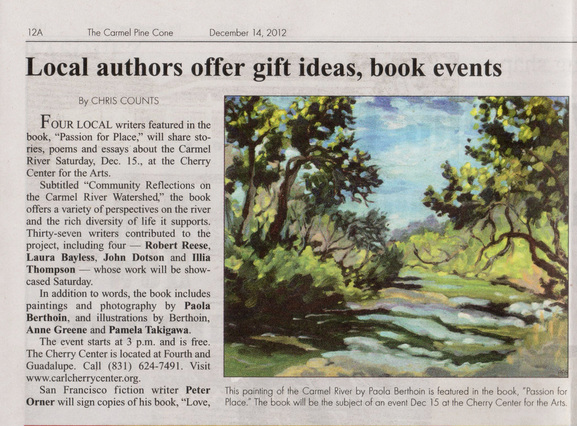

The product of grass roots creativity, the coffee-table book offers short stories, poems, sketches, essays, and a CD, plus color paintings and photographs by Berthoin, an Englishwoman who arrived in Carmel in 1965 and has never taken her eyes off the place. In more than 50 dazzling oil paintings, including “View from Carmel Valley Road,” she transforms familiar scenes into magical landscapes with bold, bright colors. Her “Storm Clouds, Los Laureles Grade” conjures an ominous scene that the Big Sur poet, Robinson Jeffers, might have depicted in blank verse.

In the foreword, Freeman House— author of Totem Salmon, a classic about Humboldt’s Mattole River—distinguishes between denizens linked to the land and citizens connected to cities. He suggests that Californians might want to define themselves as inhabitants of watersheds rather than urban or suburban neighborhoods.

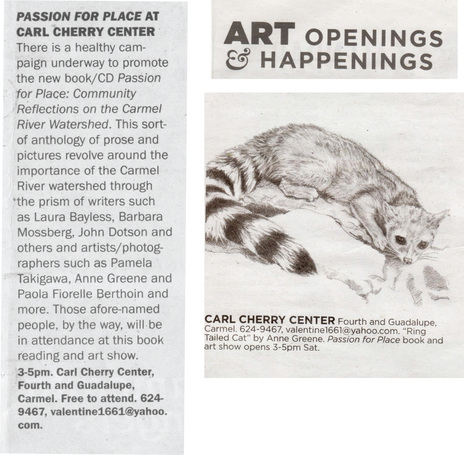

In “How I’m Taught Green,” Barbara Mossberg plunges into the vegetation around the river. “It could be a weed, wild, /How it grows by the river, free,/Unplanted by any human hand—a dart of random green,” she writes. Pam Krone-Davis aims to think and feel like a steelhead trout. “When I first hatched from the nest my mother had made in the small stones with her tail, I was very small,” she writes. Mark Stromberg keep track of the animals in and around the river, including a ring-tailed cat that looks in the artist’s rendition like a creature from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Stromberg and fellow denizens depict the watershed as a wonderland to explore and protect—and as an expensive one, too. Inhabiting a beautiful watershed, Stromberg points out, comes with a price tag these days, in more ways than one.

At its best, Passion for Place creates a strong sense of a singular environment that is sacred to Native Americans and beloved by landscape painters such as Berthoin. Moreover, the book could serve as a guide for artists and writers who might want to explore, portray, and work to save California’s endangered watersheds, from the Sierra Nevada to the Pacific, and from urban and suburban neighborhoods to rural farmlands.

Jonah Raskin is the author of Natives, Newcomers, Exiles, Fugitives: Northern California Writers and their Work and a frequent contributor to Boom.

Images courtesy of Paola Fiorelle Berthoin: painting “View from Carmel Valley Road,” photograph “Reflections on Black Rock Creek Lake.”

On August 29, Berthoin will read from Passion for Place at Caraccioli Cellars in Carmel. Pilgrim’s Way Bookstore co-sponsors the event. On September 21, the autumn equinox, Berthoin, friends, neighbors, and fellow ecologists commemorate World Rivers Day. On September 28 and 29, Berthoin joins the annual Monterey County Artist Studio Tour with an exhibit of her landscape paintings at 15 Scarlett Road, a studio in Carmel Valley. On October 13, at the popular Carmel River Festival and Feast, sponsored by the Carmel River Watershed Council, the Carmel River Steelhead Association, and the Carmel Valley Association, Berthoin is coordinator for the plein air painting show and competition for regional artists. On her website--www.passion4place.net—Berthoin posts up-to-date information about events.

Passion for Place reviewed by Jonah Raskin for the blog of BOOM: A Journal of California -- A University of California Press publication --

Like rivers, books can take time to reach their destinations. Published in 2012 after years in the making, Passion for Place—a compendium of art, essays, and interviews—is finding a niche close to the river that inspired it.

Paola Fiorelle Berthoin, the editor and driving force behind the book, is taking the book this August, September, and October, along with her own paintings and photographs, to events around Monterey County. The literary Carmelites Mary Austin and George Sterling, who lived in the watershed a hundred years ago, would likely join the festivities if they were around today. So would their summer guests, Jack and Charmian London, who often visited from Sonoma. Jack London raved about Carmel; he’d probably rave about Passion for Place. Like his best books, it takes readers on a journey, in this case inland, upstream, and into a watershed.

The product of grass roots creativity, the coffee-table book offers short stories, poems, sketches, essays, and a CD, plus color paintings and photographs by Berthoin, an Englishwoman who arrived in Carmel in 1965 and has never taken her eyes off the place. In more than 50 dazzling oil paintings, including “View from Carmel Valley Road,” she transforms familiar scenes into magical landscapes with bold, bright colors. Her “Storm Clouds, Los Laureles Grade” conjures an ominous scene that the Big Sur poet, Robinson Jeffers, might have depicted in blank verse.

In the foreword, Freeman House— author of Totem Salmon, a classic about Humboldt’s Mattole River—distinguishes between denizens linked to the land and citizens connected to cities. He suggests that Californians might want to define themselves as inhabitants of watersheds rather than urban or suburban neighborhoods.

In “How I’m Taught Green,” Barbara Mossberg plunges into the vegetation around the river. “It could be a weed, wild, /How it grows by the river, free,/Unplanted by any human hand—a dart of random green,” she writes. Pam Krone-Davis aims to think and feel like a steelhead trout. “When I first hatched from the nest my mother had made in the small stones with her tail, I was very small,” she writes. Mark Stromberg keep track of the animals in and around the river, including a ring-tailed cat that looks in the artist’s rendition like a creature from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.

Stromberg and fellow denizens depict the watershed as a wonderland to explore and protect—and as an expensive one, too. Inhabiting a beautiful watershed, Stromberg points out, comes with a price tag these days, in more ways than one.

At its best, Passion for Place creates a strong sense of a singular environment that is sacred to Native Americans and beloved by landscape painters such as Berthoin. Moreover, the book could serve as a guide for artists and writers who might want to explore, portray, and work to save California’s endangered watersheds, from the Sierra Nevada to the Pacific, and from urban and suburban neighborhoods to rural farmlands.

Jonah Raskin is the author of Natives, Newcomers, Exiles, Fugitives: Northern California Writers and their Work and a frequent contributor to Boom.

Images courtesy of Paola Fiorelle Berthoin: painting “View from Carmel Valley Road,” photograph “Reflections on Black Rock Creek Lake.”

On August 29, Berthoin will read from Passion for Place at Caraccioli Cellars in Carmel. Pilgrim’s Way Bookstore co-sponsors the event. On September 21, the autumn equinox, Berthoin, friends, neighbors, and fellow ecologists commemorate World Rivers Day. On September 28 and 29, Berthoin joins the annual Monterey County Artist Studio Tour with an exhibit of her landscape paintings at 15 Scarlett Road, a studio in Carmel Valley. On October 13, at the popular Carmel River Festival and Feast, sponsored by the Carmel River Watershed Council, the Carmel River Steelhead Association, and the Carmel Valley Association, Berthoin is coordinator for the plein air painting show and competition for regional artists. On her website--www.passion4place.net—Berthoin posts up-to-date information about events.

May 21, 2013

Passion for Place featured in Off 68, the Salinas Californian weekly paper mailed to 7,000 homeowners.

'Passion for Place' wins bronze award

by Robert Walch

The inspiration for a major artistic project often comes when one least expects it. For artist Paola Fiorelle Berthoin, that pivotal moment came while she was working on a painting in a dry segment of the Carmel River. Berthoin and some friends had been thinking about doing a book focusing on the river and the importance of the watershed, but the idea had stagnated a bit, like some of the pools of water around her. On this day, the Carmel Valley resident said she decided it was time to move forward and launch the project.

The fruits of that decision and Berthoin’s determination to make an “interesting idea” a reality is a book titled “Passion for Place: Community Reflections of the Carmel River Watershed,” which was released late last year.

How the book’s editor went from wanting to do a work of this nature to seeing it actually become a reality is a meandering story that resembles the winding course of the river the volume celebrates with art, poetry and personal narratives.

Born in England, Berthoin relocated to the Carmel Valley when she was four years old. She attended local schools and studied printmaking at what is now the California College of the Arts in Oakland. With a BA in fine arts in hand, Berthoin returned to the Central Coast, where she opened a restaurant in the valley with her mother and pursued her art career.

Berthoin became politically involved with watershed awareness when, in the late 1980s, the Hatton Canyon freeway controversy was drawing in many community members.

“Because of where I live I have always been interested in watershed issues and I was always looking for ways of using my art background to educate people,” Berthoin said.

The artist created the Hatton Canyon Arts marathon, where individuals painted in the canyon for a week to raise the public’s consciousness about the area’s natural beauty and then their works were displayed at the Carmel Crossroads.

Next, in the late 1990s, Berthoin served on the Carmel River Watershed Council, which brought together stakeholders from throughout the river’s watershed. She represented the education/spiritual/cultural stakeholders.

Since she was also involved in arts education at the time, Berthoin created a Watershed Arts curriculum that she taught in local schools, and she was also involved in creating educational boards about the watershed that were placed in Garland Park.

Berthoin, with other concerned individuals, then created an organization called RisingLeaf Watershed Arts in 2001. “The idea was to utilize the arts to inspire people to care about where they live,” she explained. “We created a very useful watershed learning map, sponsored a couple of watershed festivals in the valley and launched a storm drain stenciling campaign with a valley service club.”

All of these activities were the “precursors” to the book. The book discussion began in 2004 when Berthoin was serving as the group’s board president. The following year she took a break and the book idea was put on the back burner.

John Dotson, Peter Moras and Marliee Childs were part of the original group that discussed what shape the book should take. In 2009 Berthoin decided it was time to resurrect the idea and move ahead. At that point she decided to do it on her own.

Acting as editor in tandem with Dotson and Laura Bayless, Berthoin began contacting people whom she hoped would contribute poetry or personal narratives about the Carmel River watershed. Ultimately more than 35 people provided textual material for the volume.

The process took about two years. Berthoin provided the color paintings and photos featured in the book, while Anne Greene and Pamela Takigawa created many of the line drawings.

Since some people were not comfortable sharing their thoughts in written form, Berthoin did interviews with eight people and created a CD of excerpts from the conversations, which is included with the book.

“It is a little bit poetry, a little reminiscence and oral history,” she said. “I felt these were voices that should be heard.”

When it came to finding a publisher, Berthoin decided it made more sense to publish the book herself, thus maintaining full control of the editing process. She used a local printer in Watsonville and defrayed some of the expense through a fundraising campaign.

The initial response to “Passion for Place” has been very positive. The book’s editor said through book signings and other community events she has sold nearly half of the initial press run of 1,000 copies.

Last month, Berthoin was delighted to learn that the book was awarded a bronze medal in the Independent Publishers Competition for the Best Regional Non-fiction book for the West Pacific Region. There were 74 books entered in the category. The award will be presented at the end of May in New York City.

Berthoin also said she is open to speaking about watershed issues or doing book signings. When a book signing is scheduled, she asks some of the individuals who contributed to the book to attend and read selections of their work.

Copies of “Passion for Place: Community Reflections on the Carmel River Watershed” are available at passion4place.net.

Passion for Place in Cedar Street Times, May 10, 2013

Click here and triple click on page to read article

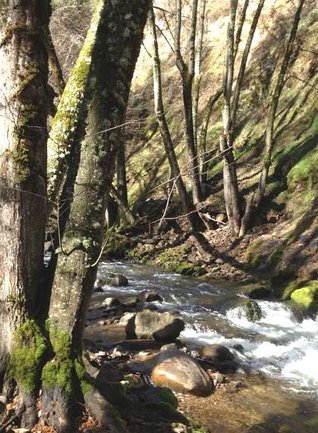

Carmel River below

the Los Padres Dam:

Photo by Marie Butcher

A Celebration of the Carmel River at Various Locations

When: Saturday, March 23, 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m

With all the news about water supply and the Carmel River, it’s easy to lose sight of the riparian environment itself—the river that pulses like blood from its Santa Lucia headwaters to the mouth of Carmel Valley, giving life to the entire Monterey Peninsula. Today’s celebration (intentionally near International Rivers Day, World Water Day and the Spring Equinox) honors and recognizes the river’s value from the time of its earliest Ohlone inhabitants to present. Participate in an opening ritual at the Birthing Rock, hike along the river, share poetry and reflect, closing with ceremony at the Carmel Lagoon. The event, sponsored by the Carmel River Watershed Conservancy, is a collaboration Passion for Place author Paola Berhoin and Green Heart Works founder Marie Butcher. [KA]

9:30am Los Padres Dam, 1:30pm Carmel River at the east end of the River Trail/East Garzas Road, 3:30pm Carmel River Lagoon. Full day $15/adults and youth, Free/children under 12, Free/Carmel River Beach portion only. Visit Facebook page for info on carpools to Los Padres Dam. Come ready to hike with your own lunch and water, journal and good intentions. 915-2706 or 624-9467.

Article from Monterey County Weekly, March 21, 2013

When: Saturday, March 23, 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m

With all the news about water supply and the Carmel River, it’s easy to lose sight of the riparian environment itself—the river that pulses like blood from its Santa Lucia headwaters to the mouth of Carmel Valley, giving life to the entire Monterey Peninsula. Today’s celebration (intentionally near International Rivers Day, World Water Day and the Spring Equinox) honors and recognizes the river’s value from the time of its earliest Ohlone inhabitants to present. Participate in an opening ritual at the Birthing Rock, hike along the river, share poetry and reflect, closing with ceremony at the Carmel Lagoon. The event, sponsored by the Carmel River Watershed Conservancy, is a collaboration Passion for Place author Paola Berhoin and Green Heart Works founder Marie Butcher. [KA]

9:30am Los Padres Dam, 1:30pm Carmel River at the east end of the River Trail/East Garzas Road, 3:30pm Carmel River Lagoon. Full day $15/adults and youth, Free/children under 12, Free/Carmel River Beach portion only. Visit Facebook page for info on carpools to Los Padres Dam. Come ready to hike with your own lunch and water, journal and good intentions. 915-2706 or 624-9467.

Article from Monterey County Weekly, March 21, 2013

Hawk drawing by Pamela Takigawa

November 29, 2012

Passion for Place Book Launch in the Monterey County Weekly

November 18, 2012

Passion for Place Book Launch in the Monterey Herald.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

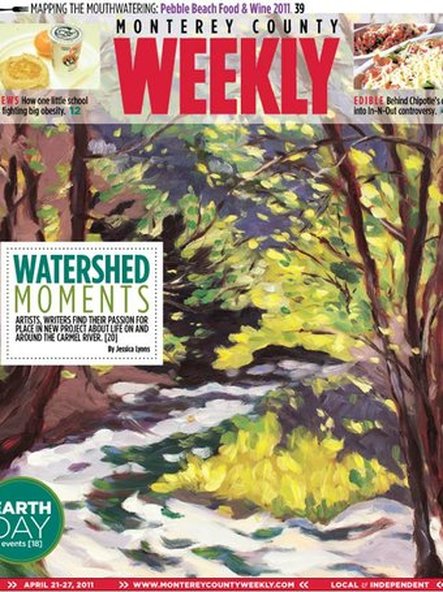

The following article was the feature cover article in the Monterey County Weekly, April 21, 2011.

DOWN TO THE RIVER The physical and emotional well-being of the Carmel River Watershed—and those who love it—comes to life in a new, collaborative project.

By Jessica Lyons

Thursday, April 21, 2011

“Fish are not just fish,” says painter Paola Fiorelle Berthoin. They connect us to the seasons, and the watershed where they live. During the winter months, they swim in from the ocean and up the Carmel River and its tributaries to spawn. The eggs hatch in the spring, and when they’re mature enough, the juvenile steelhead swim back downstream to the ocean to repeat the cycle. “If the fish aren’t there,” she continues, “we lose more and more of a connection to the natural world. That can also apply to the trees, the wildlife.”

Indeed, the Carmel River watershed holds special meaning to local artists, wildlife enthusiasts, Native Americans and many others who tell their stories in Berthoin’s upcoming book Passion for Place: Community Reflections on the Carmel River Watershed. It’s a collection of stories, essays and poems, along with paintings by Berthoin and an audio CD with interviews and natural sounds from the watershed.

Its intent: “To help bridge the gap from the river and its tributaries being seen as only a resource to the living entity that it is,” Berthoin says. “To act as an example for people in other communities as to how the stories people tell can help conserve and care for the land and rivers that sustain us all.”

Berthoin – and, really, all of Carmel Valley, if not the entire county – has a deep connection to the watershed. Berthoin lives in a home her mother built there in the mid-1970s. It’s her painting studio, and its ponds are a haven for the endangered red-legged frog. The river (along with rainwater from Berthoin’s roof that’s stored in four, 3,000-gallon tanks on her property) feeds the ponds; the artist has worked in some capacity or another to save the watershed for more than a decade.

It’s also politically charged. It’s one of our last wild places, where foxes and hawks share pricey real estate with well-heeled environmentalists and those that can afford to build ranchettes and wineries. It doesn’t have its own seat on the Board of Supervisors and the battle between development and open space is regularly fought in court. Plans for subdivisions, shopping centers and even a highway have rallied troops on both sides of the issues. Additionally, the Carmel River, a historic water source for the Monterey Peninsula, is being overpumped. The state has told the water company to stop, but the community can’t agree on a new water supply project.

The politics of place is important, Berthoin says. But – she hopes – art and poetry can unite, which is why she felt compelled to compile this book. “I can’t say this will trump the political stuff, but I hope it can provide inspiration and help reconnect people to what is special about this place. When we cut ourselves off from our creative aspects, we cut ourselves off from the natural world and our own wildness.”

Berthoin believes art can draw people together, and strip away some of the political edginess by exposing them to something beautiful. “Maybe it doesn’t have to become ugly and political. Or maybe that’s just wishful thinking on my part.”

Berthoin’s own history ebbs and flows with that of the river.

“It was the summer of 1965 when my mother brought my sisters and me to Carmel Valley from London, England,” begins her story, titled “Connection” in the book. At the time, she was 4 years old.

Berthoin tells of riding her Shetland pony, Pegus, “through the sandy fields of sapphire blue bachelor’s buttons, and along the pungently scented redwood trails and creek in Robinson Canyon,” and playing Cowboys and Indians with her sister on the rocky river banks, and catching frogs, “no bigger than a baby’s thumb, feeling the little wet points of contact of their delicate webbed feet in our cupped hands.”

It’s a nostalgic, sensory delight. But development plans lurked, hidden under the hay piled high in fields where the sisters played.

In the early ’70s, a court told all the neighborhood’s horse owners that they had to move their animals. “This was all based on one person’s complaint that the horses brought too many flies,” Berthoin writes. “The real reason was because of plans to develop the fields into a golf course and condominiums.”

Today, the nearly 500-acre property is Carmel Valley Ranch, a golf and tennis resort with a hotel and spa, restaurants and a lounge, that also plays host to weddings and corporate events. It’s an exquisite property, but one that’s far removed from the wild ranchland where Pegus used to gallop.

The family moved to Bernwick Canyon at mid-valley in 1974 to Berthoin’s current home. Drive through the suburban Tierra Grande homes, down a steep hill and there it sits on seven acres, flanked on both sides, as Berthoin writes, by native grasses, coast live oak, California sage, coyote brush, sticky monkey and, of course, poison oak.

She describes her land, where the natural and man-made world meet, in her story: “This land is a haven for migrating and resident birds including a pygmy owl, native bees, honeybees, and bumblebees. Bobcat, gray fox, cottontail rabbits and black-tailed deer make trails throughout the coyote brush and poison oak. The low guttural sound of the endangered red-legged frog and, in contrast, the cacophonous Pacific tree frogs make themselves known in the spring during mating season. Multitudes of Western fence lizard families, blue skinks, and alligator lizards sun themselves in winter and summer. Gopher snakes make their home in my gardens, helping keep in check the rodent population. A few years ago, a king snake passed through my back yard garden right at my feet as a friend and I were working on an art project! Rattlesnakes also make themselves known with their tell-tale rattle that makes one’s heart pound, although they are not as common a sighting as they once were when we moved to this land 37 years ago. Mergansers, green heron, and great blue heron check my ponds, searching for fish. Coyotes and mountain lions have also passed through. Not long ago a deer was left by the side of the house, leg ripped off. We moved the deer to a shallow depression in the ground up in the pine trees. Not more than five days later was it all gone… ”

The county moved the historical markers and widened Carmel Valley Road to four lanes in the late ’70s. “Asphalt now seals the lower Berwick canyon floor, a wide concrete sluice for the water drainage, and a road was cut into the hill.” An 8-foot-tall fence closes off the land adjacent to Berthoin’s property.

As the land becomes “gentrified and habitat destroyed,” Berthoin writes that she feels like “the mountain lion who needs a range of 35 to 100 square miles to live. Deprivation of the land that feeds my soul also feeds the mountain lions and keeps the chain of the food web intact. How can we come to a place of understanding how necessary wild land is to our well-being, just as it is for wildlife? Or has this understanding been irrevocably lost?”

A secretive ring-tail cat appears “like a ghost” in one essay. Esselen, Salinas, Chumash, Mutsen and Cherokee walk in prayer for the river as voters say no new dam in a poem. In another story, thrill seekers navigate the rapids in wetsuits and inner tubes.

And a hydrologist sets off to explore the 225-square-mile watershed, hikes into Pine Valley past fields of lupine, black oaks and blue sky and finds a cabin that belongs to a wise old man named Jack English, who invites him inside for tea and shows him his hand-carved violin bows inlaid with abalone.

This happened to Thomas Christensen seven years ago and he writes about it in his story titled, “A Watershed Experience.”

“You can conceptualize it more than other watersheds that might be larger, and for me it’s exciting to think of the connections of the land; for example, how the watershed backs up to other watersheds such as Big Sur River and Little Sur River, knowing those places and how the trails connect those areas, how waterlines drain and where the waters end up.”

“If I poured my bottle to the right of the trail it would end up in Church Creek and then eventually the Arroyo Seco River,” he writes. “If I poured my bottle to the right of the trail it would end up in the Miller Fork of the Carmel River.”

Christensen lives in Monterey and has worked in Carmel Valley since 1995, doing restoration work on the Carmel River for Monterey Peninsula Water Management District. He understands the beauty of the place – and the politics.

“The politics are pretty intense around the Carmel River in terms of it being a source of water for the community, and a lot of pushing and pulling of how much water should come from the river and how much should stay for fish and wildlife. That’s fairly controversial,” he says. But he adds Berthoin’s approach of trying to connect people to the watershed through art drew him in. “If you can get people to think and identify with the resources in the watershed, then hopefully they will make the right decisions politically.”

When Berthoin first approached her cousin, Deborah Whittlesey Sharp, about writing for the book “I though, ‘Well, no. I don’t live in the Valley. I don’t have a connection with the river.’ I said, ‘The only part of the river I have any connection to is the lagoon.’”

Sharp was born and raised in Carmel. She graduated from Carmel High School, attended Mills College and then lived on the East Coast for a dozen years before coming back to Carmel in ’81. She now lives in her old childhood home. And in her essay, “Carmel River Lagoon,” she recalls learning to swim, sunny family picnics with Orange Crush.

“I realize now that most of what I know first-hand about nature I learned from the lagoon,” she writes. “I learned the difference between the river environment and the beach environment by feeling the rough sand of the beach and the fine silt the river brought down from the valley. I loved the feel of that soft silt when I wriggled my toes in it under water.”

Starting in 2005 and spilling over into 2006, Berthoin went down to the mouth of Carmel River every Friday and painted two small water colors, about 4 inches by 6 inches. These paintings chronicle the river changing with the seasons. “It’s a real dynamic place,” she says. “There’s always something exciting happening – or it can be calm and peaceful. I love the way the river is always changing, even if we were helping it change – it’s gonna do what it’s gonna do.”

And, over the course of history, we’ve done plenty to help it change, from using it to irrigate crops and then, thousands of years later, golf courses, to damming it, to drawing water off of it through wells and manually breaching the lagoon.

Berthoin’s involvement in watershed awareness began in 1998 with Hatton Canyon. State plans dating back to 1952 called for a freeway through the canyon; nearly four decades later, a group of locals calling itself the Hatton Canyon Coalition launched an effort to block CalTrans’ plans. (In 2002, then-Gov. Gray Davis formally killed the freeway when he signed the land over to California State Parks.)

Rep. Sam Farr tasked Supervisor Dave Potter with forming a Watershed Council, including representatives from agriculture, hospitality, environmental and residential groups, and educational and cultural organizations, among others. Potter appointed Berthoin as the educational and cultural stakeholder.

In 2001, she formed RisingLeaf Watershed Arts (www.risingleaf.org), an intersection of art and sustainability.

“The purpose was to have a much clearer voice on behalf of the arts and the connection between the arts and the natural world that we depend on,” Berthoin says. “I very much wanted to create an organization that could put something out there that was positive, using the arts to enliven people to care for where they live.”

The nonprofit painted a mural of the Northern Salinas Valley Watershed at Salinas’ Kammann Elementary School, consulted on the school’s landscape design and helped plant three native plant gardens. It sponsored nature study and landscape painting events for kids and families, worked with on-campus student groups, organized art shows and poetry readings and participated in clean-up days.

But by 2004, Berthoin was already thinking about creating a book. “By the end of 2005, I felt I needed a real break, and things stopped at that point.”

She needed an escape from the day-to-day desk job and wanted to reconnect with the natural aspect of watershed protection – and the weekly watercolor sessions were born. “I found that going out and doing a creative thing really helped to ground me, being in the watershed and not getting totally lost in the busy work of running an organization.”

Berthoin had always wanted to hike the entire watershed; en lieu of that, she decided to hike the accessible ridges and peaks and between 2008 and 2009, she painted her Watershed Series, a collection of 30 plus oil paintings from various vantage points. The canvases show her route: Berthoin started at Jacks Peak, looking down on Point Lobos. She traveled along the northern side of the watershed – from her northernmost point, looking down into Pine Valley atop Tasajara Road. She stopped along the way, on the road to Cachagua and the road to Los Padres Dam, to paint, too. She hiked into Garland Park and Kahn Ranch, and painted a couple landscapes near Carmel Valley Ranch, looking toward Rancho San Carlos. From atop Echo Ridge her view stretched over the Bay, and another painting from Palo Corona’s Inspiration Point looks out onto the ocean.

“I decided to do two more: One looking down across Hatton Canyon to Palo Corona Ranch, and the last from the same place I started, Jacks Peak looking down to Point Lobos.”

Then she moved on to her River Series, some 20 oil paintings of the Carmel River. And on July 12, 2009, as she painted the river running dry, the inspiration for the book came flooding back.

“I was down at the river at Quail Lodge and the river was drying up. Part of me was thinking, ‘I personally want to be connected with the community beyond just painting and sharing that with people. Now is the time to do it. This river needs more of a voice and we need to be able to share it.’”

In “Passion for Place,” Berthoin’s essay ends on a hopeful note.

“The other day I visited a part of the river I hadn’t been to in years, just at the end of Dorris Drive in Mid-Valley. I discovered trails through the thickets of willows out to the river running full from the winter rains and took in the musty smells of the wet earth and leaves. Light was glinting on the water, yellow and red from reflections of willows and one dogwood tree. Then, up along another trail near the sycamores and bare-twisted branches of the buckeye, a red-shouldered hawk flew out about 15 feet ahead of me. Such a special sight and gift! I quickly took out my camera and followed him from tree to tree as he called, catching a few pictures amidst the network of branches and old leaves that concealed him with his feathers and colors looking much the same. It is times like these that make living here, despite the increase of development throughout the valley, a place to be grateful for and help protect. Protect it for the delicate feathers found floating on the water, spiraling in the sky, reminding us of our own brief existence on a planet that has been here for millions of years.”

Passion for Place Book Launch in the Monterey County Weekly

November 18, 2012

Passion for Place Book Launch in the Monterey Herald.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The following article was the feature cover article in the Monterey County Weekly, April 21, 2011.

DOWN TO THE RIVER The physical and emotional well-being of the Carmel River Watershed—and those who love it—comes to life in a new, collaborative project.

By Jessica Lyons

Thursday, April 21, 2011

“Fish are not just fish,” says painter Paola Fiorelle Berthoin. They connect us to the seasons, and the watershed where they live. During the winter months, they swim in from the ocean and up the Carmel River and its tributaries to spawn. The eggs hatch in the spring, and when they’re mature enough, the juvenile steelhead swim back downstream to the ocean to repeat the cycle. “If the fish aren’t there,” she continues, “we lose more and more of a connection to the natural world. That can also apply to the trees, the wildlife.”

Indeed, the Carmel River watershed holds special meaning to local artists, wildlife enthusiasts, Native Americans and many others who tell their stories in Berthoin’s upcoming book Passion for Place: Community Reflections on the Carmel River Watershed. It’s a collection of stories, essays and poems, along with paintings by Berthoin and an audio CD with interviews and natural sounds from the watershed.

Its intent: “To help bridge the gap from the river and its tributaries being seen as only a resource to the living entity that it is,” Berthoin says. “To act as an example for people in other communities as to how the stories people tell can help conserve and care for the land and rivers that sustain us all.”

Berthoin – and, really, all of Carmel Valley, if not the entire county – has a deep connection to the watershed. Berthoin lives in a home her mother built there in the mid-1970s. It’s her painting studio, and its ponds are a haven for the endangered red-legged frog. The river (along with rainwater from Berthoin’s roof that’s stored in four, 3,000-gallon tanks on her property) feeds the ponds; the artist has worked in some capacity or another to save the watershed for more than a decade.

It’s also politically charged. It’s one of our last wild places, where foxes and hawks share pricey real estate with well-heeled environmentalists and those that can afford to build ranchettes and wineries. It doesn’t have its own seat on the Board of Supervisors and the battle between development and open space is regularly fought in court. Plans for subdivisions, shopping centers and even a highway have rallied troops on both sides of the issues. Additionally, the Carmel River, a historic water source for the Monterey Peninsula, is being overpumped. The state has told the water company to stop, but the community can’t agree on a new water supply project.

The politics of place is important, Berthoin says. But – she hopes – art and poetry can unite, which is why she felt compelled to compile this book. “I can’t say this will trump the political stuff, but I hope it can provide inspiration and help reconnect people to what is special about this place. When we cut ourselves off from our creative aspects, we cut ourselves off from the natural world and our own wildness.”

Berthoin believes art can draw people together, and strip away some of the political edginess by exposing them to something beautiful. “Maybe it doesn’t have to become ugly and political. Or maybe that’s just wishful thinking on my part.”

Berthoin’s own history ebbs and flows with that of the river.

“It was the summer of 1965 when my mother brought my sisters and me to Carmel Valley from London, England,” begins her story, titled “Connection” in the book. At the time, she was 4 years old.

Berthoin tells of riding her Shetland pony, Pegus, “through the sandy fields of sapphire blue bachelor’s buttons, and along the pungently scented redwood trails and creek in Robinson Canyon,” and playing Cowboys and Indians with her sister on the rocky river banks, and catching frogs, “no bigger than a baby’s thumb, feeling the little wet points of contact of their delicate webbed feet in our cupped hands.”

It’s a nostalgic, sensory delight. But development plans lurked, hidden under the hay piled high in fields where the sisters played.

In the early ’70s, a court told all the neighborhood’s horse owners that they had to move their animals. “This was all based on one person’s complaint that the horses brought too many flies,” Berthoin writes. “The real reason was because of plans to develop the fields into a golf course and condominiums.”

Today, the nearly 500-acre property is Carmel Valley Ranch, a golf and tennis resort with a hotel and spa, restaurants and a lounge, that also plays host to weddings and corporate events. It’s an exquisite property, but one that’s far removed from the wild ranchland where Pegus used to gallop.

The family moved to Bernwick Canyon at mid-valley in 1974 to Berthoin’s current home. Drive through the suburban Tierra Grande homes, down a steep hill and there it sits on seven acres, flanked on both sides, as Berthoin writes, by native grasses, coast live oak, California sage, coyote brush, sticky monkey and, of course, poison oak.

She describes her land, where the natural and man-made world meet, in her story: “This land is a haven for migrating and resident birds including a pygmy owl, native bees, honeybees, and bumblebees. Bobcat, gray fox, cottontail rabbits and black-tailed deer make trails throughout the coyote brush and poison oak. The low guttural sound of the endangered red-legged frog and, in contrast, the cacophonous Pacific tree frogs make themselves known in the spring during mating season. Multitudes of Western fence lizard families, blue skinks, and alligator lizards sun themselves in winter and summer. Gopher snakes make their home in my gardens, helping keep in check the rodent population. A few years ago, a king snake passed through my back yard garden right at my feet as a friend and I were working on an art project! Rattlesnakes also make themselves known with their tell-tale rattle that makes one’s heart pound, although they are not as common a sighting as they once were when we moved to this land 37 years ago. Mergansers, green heron, and great blue heron check my ponds, searching for fish. Coyotes and mountain lions have also passed through. Not long ago a deer was left by the side of the house, leg ripped off. We moved the deer to a shallow depression in the ground up in the pine trees. Not more than five days later was it all gone… ”

The county moved the historical markers and widened Carmel Valley Road to four lanes in the late ’70s. “Asphalt now seals the lower Berwick canyon floor, a wide concrete sluice for the water drainage, and a road was cut into the hill.” An 8-foot-tall fence closes off the land adjacent to Berthoin’s property.

As the land becomes “gentrified and habitat destroyed,” Berthoin writes that she feels like “the mountain lion who needs a range of 35 to 100 square miles to live. Deprivation of the land that feeds my soul also feeds the mountain lions and keeps the chain of the food web intact. How can we come to a place of understanding how necessary wild land is to our well-being, just as it is for wildlife? Or has this understanding been irrevocably lost?”

A secretive ring-tail cat appears “like a ghost” in one essay. Esselen, Salinas, Chumash, Mutsen and Cherokee walk in prayer for the river as voters say no new dam in a poem. In another story, thrill seekers navigate the rapids in wetsuits and inner tubes.

And a hydrologist sets off to explore the 225-square-mile watershed, hikes into Pine Valley past fields of lupine, black oaks and blue sky and finds a cabin that belongs to a wise old man named Jack English, who invites him inside for tea and shows him his hand-carved violin bows inlaid with abalone.

This happened to Thomas Christensen seven years ago and he writes about it in his story titled, “A Watershed Experience.”

“You can conceptualize it more than other watersheds that might be larger, and for me it’s exciting to think of the connections of the land; for example, how the watershed backs up to other watersheds such as Big Sur River and Little Sur River, knowing those places and how the trails connect those areas, how waterlines drain and where the waters end up.”

“If I poured my bottle to the right of the trail it would end up in Church Creek and then eventually the Arroyo Seco River,” he writes. “If I poured my bottle to the right of the trail it would end up in the Miller Fork of the Carmel River.”

Christensen lives in Monterey and has worked in Carmel Valley since 1995, doing restoration work on the Carmel River for Monterey Peninsula Water Management District. He understands the beauty of the place – and the politics.

“The politics are pretty intense around the Carmel River in terms of it being a source of water for the community, and a lot of pushing and pulling of how much water should come from the river and how much should stay for fish and wildlife. That’s fairly controversial,” he says. But he adds Berthoin’s approach of trying to connect people to the watershed through art drew him in. “If you can get people to think and identify with the resources in the watershed, then hopefully they will make the right decisions politically.”

When Berthoin first approached her cousin, Deborah Whittlesey Sharp, about writing for the book “I though, ‘Well, no. I don’t live in the Valley. I don’t have a connection with the river.’ I said, ‘The only part of the river I have any connection to is the lagoon.’”

Sharp was born and raised in Carmel. She graduated from Carmel High School, attended Mills College and then lived on the East Coast for a dozen years before coming back to Carmel in ’81. She now lives in her old childhood home. And in her essay, “Carmel River Lagoon,” she recalls learning to swim, sunny family picnics with Orange Crush.

“I realize now that most of what I know first-hand about nature I learned from the lagoon,” she writes. “I learned the difference between the river environment and the beach environment by feeling the rough sand of the beach and the fine silt the river brought down from the valley. I loved the feel of that soft silt when I wriggled my toes in it under water.”

Starting in 2005 and spilling over into 2006, Berthoin went down to the mouth of Carmel River every Friday and painted two small water colors, about 4 inches by 6 inches. These paintings chronicle the river changing with the seasons. “It’s a real dynamic place,” she says. “There’s always something exciting happening – or it can be calm and peaceful. I love the way the river is always changing, even if we were helping it change – it’s gonna do what it’s gonna do.”

And, over the course of history, we’ve done plenty to help it change, from using it to irrigate crops and then, thousands of years later, golf courses, to damming it, to drawing water off of it through wells and manually breaching the lagoon.

Berthoin’s involvement in watershed awareness began in 1998 with Hatton Canyon. State plans dating back to 1952 called for a freeway through the canyon; nearly four decades later, a group of locals calling itself the Hatton Canyon Coalition launched an effort to block CalTrans’ plans. (In 2002, then-Gov. Gray Davis formally killed the freeway when he signed the land over to California State Parks.)

Rep. Sam Farr tasked Supervisor Dave Potter with forming a Watershed Council, including representatives from agriculture, hospitality, environmental and residential groups, and educational and cultural organizations, among others. Potter appointed Berthoin as the educational and cultural stakeholder.

In 2001, she formed RisingLeaf Watershed Arts (www.risingleaf.org), an intersection of art and sustainability.

“The purpose was to have a much clearer voice on behalf of the arts and the connection between the arts and the natural world that we depend on,” Berthoin says. “I very much wanted to create an organization that could put something out there that was positive, using the arts to enliven people to care for where they live.”

The nonprofit painted a mural of the Northern Salinas Valley Watershed at Salinas’ Kammann Elementary School, consulted on the school’s landscape design and helped plant three native plant gardens. It sponsored nature study and landscape painting events for kids and families, worked with on-campus student groups, organized art shows and poetry readings and participated in clean-up days.

But by 2004, Berthoin was already thinking about creating a book. “By the end of 2005, I felt I needed a real break, and things stopped at that point.”

She needed an escape from the day-to-day desk job and wanted to reconnect with the natural aspect of watershed protection – and the weekly watercolor sessions were born. “I found that going out and doing a creative thing really helped to ground me, being in the watershed and not getting totally lost in the busy work of running an organization.”

Berthoin had always wanted to hike the entire watershed; en lieu of that, she decided to hike the accessible ridges and peaks and between 2008 and 2009, she painted her Watershed Series, a collection of 30 plus oil paintings from various vantage points. The canvases show her route: Berthoin started at Jacks Peak, looking down on Point Lobos. She traveled along the northern side of the watershed – from her northernmost point, looking down into Pine Valley atop Tasajara Road. She stopped along the way, on the road to Cachagua and the road to Los Padres Dam, to paint, too. She hiked into Garland Park and Kahn Ranch, and painted a couple landscapes near Carmel Valley Ranch, looking toward Rancho San Carlos. From atop Echo Ridge her view stretched over the Bay, and another painting from Palo Corona’s Inspiration Point looks out onto the ocean.

“I decided to do two more: One looking down across Hatton Canyon to Palo Corona Ranch, and the last from the same place I started, Jacks Peak looking down to Point Lobos.”

Then she moved on to her River Series, some 20 oil paintings of the Carmel River. And on July 12, 2009, as she painted the river running dry, the inspiration for the book came flooding back.

“I was down at the river at Quail Lodge and the river was drying up. Part of me was thinking, ‘I personally want to be connected with the community beyond just painting and sharing that with people. Now is the time to do it. This river needs more of a voice and we need to be able to share it.’”

In “Passion for Place,” Berthoin’s essay ends on a hopeful note.

“The other day I visited a part of the river I hadn’t been to in years, just at the end of Dorris Drive in Mid-Valley. I discovered trails through the thickets of willows out to the river running full from the winter rains and took in the musty smells of the wet earth and leaves. Light was glinting on the water, yellow and red from reflections of willows and one dogwood tree. Then, up along another trail near the sycamores and bare-twisted branches of the buckeye, a red-shouldered hawk flew out about 15 feet ahead of me. Such a special sight and gift! I quickly took out my camera and followed him from tree to tree as he called, catching a few pictures amidst the network of branches and old leaves that concealed him with his feathers and colors looking much the same. It is times like these that make living here, despite the increase of development throughout the valley, a place to be grateful for and help protect. Protect it for the delicate feathers found floating on the water, spiraling in the sky, reminding us of our own brief existence on a planet that has been here for millions of years.”